Well, “broke” is not a policy word, so it is hard to join the raging debate about the brokeness or otherwise of Ghana if one is more biased towards policy activism.

I will say this though, when Multimedia, a major Ghanaian media outlet, invited me to deliver a ten minute “statement” on an important national issue on the first edition of their primetime show, Newsfile, today, I knew I had to talk about Ghana’s finances.

Whereas “brokeness” is not rigorous enough a term for gauging the finances of a country, “creditworthiness” is. Like most businesses, most countries require debt to function. Globally, we have seen a surge of public debt for this very reason.

Globalisation means that, more and more, governments borrow from investors and savers all over the world, not just in their own countries. 17 African countries (out of 55) are today able to borrow from private investors around the globe (not just from other governments and institutions like the World Bank and IMF). How these investors view the creditworthiness of the borrowing country/government offers one of the most objective metrics in gauging the finances of any country.

Such investor sentiment can be discerned from how much they are willing to charge in interest before they lend to a government. For a while now it has become clear that compared to its African peers, international investors prefer to lend to Ghana at a higher rate, clearly a sign that they are more worried about Ghana’s “credit risk”.

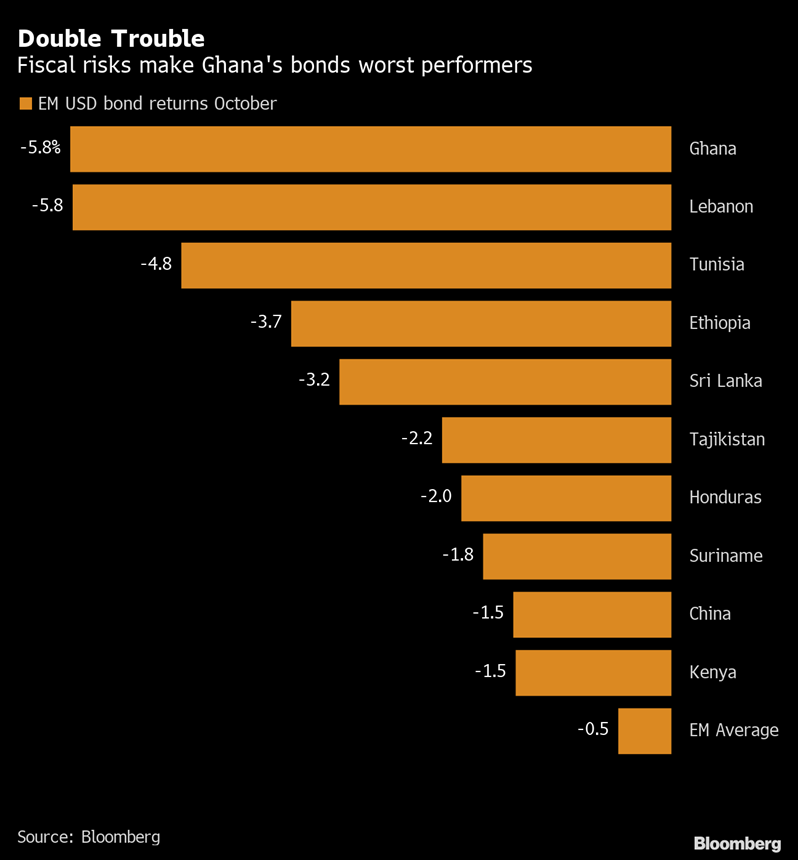

Note that this growing tendency among investors to price in higher risk for Ghanaian debt has been apparent well before COVID-19 struck. But in recent months things have come to a head and Ghana is now grouped globally with countries like Lebanon and war-troubled Ethiopia in terms of debt riskiness.

What accounts for this? Well, since the country became the first on the continent to borrow from the Eurobond market in 2007 (on the back of its first sovereign credit rating in 2003, 3 years after continental pioneer, Senegal), it has been more enthusiastic than most in frequenting the market for more. A combined oil and gold boom from 2010 onwards underwrote this appetite and increased awareness of the Ghana sovereign lending opportunity globally. Before long, all the gains from the HIPC debt relief it secured in the early 2000s had been whittled away. At the end of Ghana’s HIPC program, it owed just 1.18 times more than the revenue the government collects. Today, it owes nearly 5.4 times more.

Towards the completion point of the HIPC program in 2004, the country’s absolute spending on its debt had dropped to barely a little over $100 million. Today, the government requires a whopping $6 billion for the same purpose.

The reason is simple. Take 2021, for instance. The government needed to find $18 billion to make good on all its obligations. It could only raise $12 billion from investment, taxation and operations. An important nuance: these are “net” flows. To fully appreciate the hand-to-mouth nature of the situation, consider that in the same year it actually borrowed $5.2 billion from overseas sources, but promptly used $2.55 billion in paying back some of what it owed from previous rounds of borrowing.

In terms of the burden of debt on national finances, Ghana bears twice that of the average African country.

The announcement yesterday by Fitch, one of three major global companies that assess the creditworthiness of countries, that it will downgrade Ghana’s sovereign credit rating to B-, with a negative outlook (meaning that it is more likely to downgrade further than to upgrade) should therefore not have come as a surprise. But it is very significant for a number of reasons.

First, it can be argued that Fitch has been a bit more lenient with Ghana than some of its peer rating agencies historically. Given investor sentiment on Ghana’s credit risk, its ratings could actually have been worse than it has recently been.

Fitch’s negative outlook is particularly concerning because the B- rating places the country at the border with countries on the verge of defaulting on their debt. Any further downgrade will therefore seriously prolong the country’s shutout from the international private capital markets.

To reinforce the point, this is Fitch’s worst rating since it began covering the Ghanaian economy nearly 20 years ago. The country now has the dubious honour of joining Tunisia and El Salvador as B- peers with a negative outlook.

Ghana has already been in doldrums territory as far as Moody’s and S&P are concerned, so a negative outlook is expected across the board. That seems pretty bad, so how does the government explain things?

The general posture of the country’s economic managers has been to blame COVID for the short-term issues (though, as shown in previous sections, the malaise clearly predates COVID), and low tax compliance by the population for all the other, more chronic, problems.

The chart below summarises the government’s favourite point.

In sum, in the government’s view, Ghanaians pay too little tax compared to their compatriots elsewhere, even in other African countries. True? Maybe. But there are important nuances to note before one starts comparing apples and oranges.

Take a very good like at the countries clustered around Ghana in the chart above, i.e. Ghana’s peer tax laggards. You will notice something curious that is also borne out by the two charts below.

Even a cursory glance will tell you that high natural resource dependency and a strong extractives/commodity sector correlates roughly to lower tax-to-GDP ratios. This is intuitive. Even without the usual rigour of multivariate regression analysis, one can hint at the tendency of extractives to inflate output numbers without necessarily boosting state revenues. That this claim is not some fluke of overzealous correlationism is supported by similar findings beyond Africa.

Commodity supermajor, Australia, has a tax to GDP ratio of about 24% whilst less commodity-dependent France reports a hefty 45%. An even better contrast can be got when one compares two economies similar in many respects except in relation to the scale of their commodity involvement. Norway hovers around 25% for our metric of interest, whilst Denmark has been known to breach the 48% mark.

It is very unlikely that such large differences between Australia and France, Denmark and Norway, or Brazil and Uruguay, can be put down merely to tax collection efficiency or citizen compliance. Nor, clearly, is this strictly a matter of absolute diversification of the economy.

In light of the above, it is reasonable to argue that compared with its true peers on the African continent, Ghana’s tax take (which by the way has now converged with the Sub-Saharan average of about 15%) is pretty unremarkable. Exceptionally low tax revenue for the size of the economy cannot be the reason why the country’s creditworthiness is taking such a hit.

Misdiagnosing the problem however leads to half-baked ideas such as the e-levy, which we have discussed at length here and here. I will sum up our previous conclusions as follows:

- The Government’s estimate of making $1.15 billion from the e-levy is overly rosy. Countries like Kenya have been using similar taxes for more than 10 years. Uganda went the same route more than 3 years ago. None of them have been able to rake in fantastical sums. MTN, responsible for 92% thereabouts of transactions in the Ghanaian mobile money space makes about $216 million from unit fees. Adjusting for the facts that Uganda has a fifth of Ghana’s mobile money transactional scale and that it applies less than one-third of Ghana’s proposed rate, Uganda’s $27 million per annum take may translate to about $350 million in Ghana’s case. Far from making a dent in a $6.5 billion fiscal hole. In sum, e-levy is not a major part of the answer.

- The current design of the e-levy lacks any backing in serious modelling. Its elements are purely arbitrary. If that remains the case, the tax could seriously distort behaviour and drive the emerging digital economy and its players more into the informal rather than the formal bracket. This will undermine larger digital taxation strategies currently being designed by the Ghana Revenue Authority with the help of the British Government. As more business shifts to currently informal digital channels like Instagram, WhatsApp and TikTok, careful thinking is required to figure out how to craft policies for e-commerce that don’t end up burdening the few formal operators.

- Presently, digital money is mostly used to drive off-line transactions. To truly deepen the country’s digitisation drive, smarter strategies are needed to boost in-app purchases and online transactions. A cleverer digital taxation strategy can achieve that. A blunt instrument will only deepen the cash-like use of digital money, thus forgoing the true benefits of digitisation.

Moreover, overconcentrating on tax compliance and collection can distract from other important features, especially when misdiagnosis leads to drawing the wrong lessons from other jurisdictions. For example, one major compositional difference between the rich world and places like Ghana, as far as tax structure goes, is the former’s strong reliance on social security taxes, which reflect demographic and industrial factors that don’t apply in Africa.

Another design blind spot created by excessive focus on collection alone is the tendency not to look at categories of taxation that already constitute major sources of revenue, like VAT. Yet, research shows that Ghana’s VAT structure is rather inefficient.

Add to the above the issue of “exemptions” that has never really benefitted from broader stakeholder consultation and the scale of neglect becomes even clearer.

Indeed, poor stakeholder engagement accounts for the inability of the government to take on public spending, by far the most critical gap to be filled if Ghana is to climb out of its current revenue crisis. Because the government never genuinely invites stakeholders to contribute to policy formulation and merely pretends to listen and then goes ahead to do what it always intended to do anyway, cross-elite buy-in tends to be weak. When painful sacrifices are required, it suddenly becomes obvious to everyone that the government simply does not have the necessary credibility to rally the population.

Furthermore, the government and bureaucratic classes are themselves not genuinely interested in tackling waste in public spending head on. Genuine cooption of independent-minded stakeholders in the academic, civil society and opposition benches in Parliament would lead to hard questions the government has no appetite for.

For example, Civil Society Organisations would insist on truly independent evaluation of a whole raft of government programs that have become mere troughs of patronage for the politically connected. They will ask for a thorough, rigorous, non-partisan review of the more than 40 so-called youth employment programs in Ghana, and demand evidence that they are indeed adding value.

The last time a government slipped and allowed such an independent review, it was discovered that as much as $317 million may have been wasted in one program – GYEEDA – alone.

Whilst the government spends tens of millions of dollars on so called entrepreneurship and employment schemes that it refuses to subject to a truly multistakeholder review, the one area that serious research has established could make a genuine dent in youth unemployment – technical & vocational education (TVET) – continues to suffer neglect.

For decades, TVET has received less than 2% of the total education budget. Whilst the government was busy pouring millions of dollars into evident scams like the so-called “venture capital trust fund” (where officers invented fictitious companies and used them to pocket the cash), purportedly to resource entrepreneurship as a solution to unemployment, it was also sashaying around Accra, cap in hand, begging the likes of DANIDA for $14 million to invest in youth technical skills.

Clearly, the issue is not that Ghana is broke but that it is broken. To mend its broken policymaking and restore the country to creditworthiness, the government and its enabling political class must admit the brokenness of the current public finance model and solicit genuine multistakeholder support to cut another path.